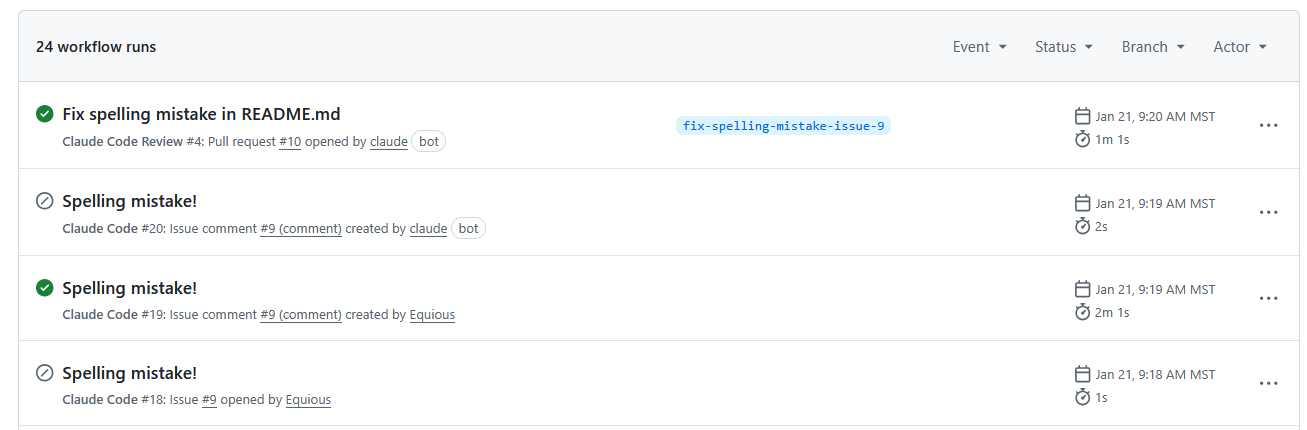

Automated workflow runs triggered by an AI coding agent (“Claude Code”) for a trivial spelling fix. The agent opened an issue, posted a checklist comment, and then created a pull request. The final “Fix spelling mistake” PR run took about 1 minute to handle a one-line change.

Recently, we experimented with using an AI-based coding agent to fix a tiny typo: changing "applicasion" to "application" in a README. What we found was a significant mismatch between problem and solution. The agent went through a whole workflow – listing issues, posting a checklist comment, creating a new branch, committing the change, opening a pull request, and even pondering if a code review was needed. By the end, it consumed over 21,000 input tokens (roughly equivalent to reading a short novel) just to make that one-line edit.

It's a clear example of tool-task mismatch. The logs show how the process ballooned far beyond the scope of the task. This isn’t a knock on the AI’s capabilities; it’s a reality of how these AI coding agents work right now. They bring a lot of overhead even for the simplest changes. Let’s unpack why that happens, and what others have observed about this phenomenon.

There are a few reasons an AI agent can end up being expensive and slow for small changes:

You can see here just how much the bot is doing, simply to decide that a README change doesn’t require a code review.

The result of these factors is that using an AI agent for something very small can be impractical or impossible to scale. It works, but it’s inefficient. Our internal trial vividly demonstrated that inefficiency: minutes of run time and tens of thousands of tokens to accomplish what one person could do in 30 seconds with an editor.

Our experience isn’t an isolated case. Early adopters of AI coding assistants have noticed the same pattern. Many have shared candid feedback about when these tools shine and when they falter. A common theme: if not set up with the right tooling and scope, an AI can introduce more overhead than it removes, especially on trivial tasks.

For instance, one programmer recounts spending hours guiding an LLM through code with ultimately frustrating results, concluding that “the mental overhead of all this is worse than if I just sat down and wrote the code”[7]. That sentiment will sound familiar to anyone who’s wrestled with an AI that keeps missing the point on a minor fix. There’s a threshold where the time spent explaining, re-prompting, and verifying the AI’s output outweighs the time it would take to just do it manually. Small bug fixes or tweaks often fall below that threshold.

It’s also noted that LLMs can be surprisingly adept at certain things (explaining code, sketching out a solution) while struggling to efficiently produce correct small edits. Without good supporting tools, one Reddit user argued, “you frequently get stuck for extended periods on simple bugs… usually the mental gymnastics of prompting and checking are worse than the fix itself”. In our case, prompting the agent to fix a simple typo and then verifying all its procedural steps was far more convoluted than the direct fix.

Another perspective comes from those building and using multi-step coding agents professionally. Greg Ceccarelli, an early pioneer in AI-driven development, pointed out that “each agent turn might warrant commentary or a new commit. The overhead can be enormous if not carefully managed.”[8] In other words, every extra cycle the agent takes (adding a comment here, a commit there) is an opportunity for bloat. If we don’t streamline the agent’s workflow, it will do a lot of unnecessary work because it doesn’t intuitively know which steps are essential versus overkill.

The good news is that these pain points are leading to best practices. Developers are learning when not to use the heavy AI hammer. One illuminating write-up by Allen Pike described how the initial hype around the biggest, “smartest” models died down because they “were ultimately too expensive and slow to be worth the squeeze for day-to-day coding.”[9] Many found that for routine development, the cost in API calls and time didn't justify the convenience, particularly for straightforward tasks. Pike’s solution was to reserve the really powerful (and costly) models for truly complex problems, and use cheaper or no AI for the rest. He even experimented with spending $1000/month on an advanced model for a period, and found it could be justified for difficult, high-impact coding, but he still advises not to waste expensive model cycles on trivialities[10][11].

Crucially, he emphasizes using deterministic tools for deterministic problems: “Shifting errors from runtime → test-time → build-time makes everybody more productive. Even better, fix issues deterministically with a linter or formatter. Let your expensive LLMs and humans focus on the squishy parts.”[11] A typo in documentation is the definition of a non-squishy problem. It’s straightforward, deterministic, and easily caught by a spellchecker. That’s a task begging for an automated script or a quick manual edit, not a deluxe AI treatment.

Others have echoed this: if an LLM-driven agent finds itself doing the same kind of small fix over and over, you’re better off automating that pattern outside the LLM. In a discussion about coding agent loops, one commenter put it this way: if you notice an AI agent frequently invoking a series of tool calls to solve a recurring problem, you should pull that sequence out into a normal function or script and “bypass LLMs altogether” for that case[5]. Essentially, cache the solution so the AI doesn’t reinvent the wheel every time. This approach reduces redundant prompt calls, saving time and money.

All of these community insights underline a key point: AI coding assistants are not a silver bullet, and they can introduce significant overhead on trivial tasks. Being aware of that is the first step toward using them intelligently.

There of course exists a significant financial cost to consider when using AI for development. Most advanced models (OpenAI’s GPT-5.2, Anthropic’s Claude, etc.) charge per token or per request. A fraction of a cent per API call seems negligible, but those calls multiply quickly, especially when AI handles numerous small tasks in an automated pipeline.

Our spelling-fix experiment cost only a few dimes, but imagine that at scale or with a larger codebase. It’s not hard to see how cost can balloon when AI is mis-applied. An extreme (but instructive) example: OpenAI’s pricing for GPT-3.5 at one point was about $0.002 per ~750 words. A DoorDash engineer calculated that if they applied that to 10 billion predictions a day (DoorDash scale), it would be $20 million per day in API fees[17]. That's an extreme scenario, but it highlights how per-call costs compound at volume. Even at a smaller scale, companies have reported significant expenses: one logistics firm replaced a GPT-4-powered solution with a smaller 7B-parameter model and saw their per-query cost drop from ~$0.008 to ~$0.0006, saving about $70,000 per month[18]. The key insight is that bigger models are more expensive (in API fees and in required infrastructure), so you want to avoid paying those rates for trivial work that a simpler method could handle.

A major contributor to cost is the token usage overhead we discussed. Longer prompts, more context, and multiple back-and-forth turns all consume tokens that you get billed for. If 80% of those tokens are “overhead” (as one report suggests is common), then 80% of your money is being spent on overhead too. For instance, our Claude agent used ~23,000 tokens to fix the typo. If we estimate Claude’s pricing similar to OpenAI’s (~$0.016 per 1K tokens for input on a large model), that one typo fix cost around $0.37 just in token billing. We actually measured ~$0.23 for the fix and $0.09 for the review step, which aligns with that ballpark. Again, pennies in isolation, but it’s the principle: paying cloud compute to do something a human could do almost for free (and faster). Over many such micro-tasks, or in an agent that runs continuously, those pennies add up to real dollars.

There’s also the consideration of compute resources and energy. Running a big model for a small task can be substantial overkill. Smaller, more efficient models or solutions can often achieve the same result with a fraction of the compute. This is why AI practitioners advocate for techniques like model distillation and multi-model architectures. For example, one strategy is to route simple requests to a small model and only use the big model for complex queries[19]. By doing this, companies have reported being able to cut LLM costs by 80–90% while maintaining performance[20]. In the context of coding: you might use a lightweight code analysis for straightforward linting or formatting changes, saving the heavy LLM for when you truly need a deep reasoning about code. The bottom line is that efficiency matters. If you wouldn’t pay a senior engineer for 5 hours of work to fix a typo, you probably don’t want to pay for 5 minutes of a 500-billion-parameter model’s time either.

So how can we get the best of both worlds? A few strategies emerge from our research and experience:

AI coding tools offer substantial productivity benefits for the right problems. They can draft entire modules, refactor legacy code, and boost our productivity in ways we couldn’t imagine a few years ago. However, as we’ve seen, throwing a big AI model at a small problem can be counterproductive, leading to slower results, wasted compute, and higher costs for negligible benefit. The good news is that awareness is growing in the developer community. We’re learning to be more nuanced in how we use these tools, combining human judgment with AI assistance in smarter ways.

In the end, the goal is to make our workflow both efficient and effective. That means using AI where it truly adds value and not out of habit or hype. If a task takes a minute to code manually, you're likely better off doing it directly than spending five minutes in an AI workflow. On the other hand, if you’re facing a complex algorithm or an unfamiliar domain, that might be the perfect time to enlist your AI pair programmer. By balancing these approaches, teams can avoid the trap of "AI for AI's sake" and maximise the return on their tooling investments.

At Cyfrin, we evaluate development tools, including AI assistants, through a security-first lens. For teams building in web3, understanding the strengths and limitations of your tooling is essential for maintaining code quality and security standards.

Whether you're integrating AI into your development workflow or evaluating its impact on your security practices, our team can help you make informed decisions.

Contact Cyfrin to discuss your development and security needs with a member of the team.

Sources:

[3] [4] Why Tightly Coupled Code Makes AI Coding Assistants Expensive and Slow | by ThamizhElango Natarajan | Dec, 2025 | Medium

[5] The unreasonable effectiveness of an LLM agent loop with tool use | Hacker News

https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=43998472

[6] [9] [10] [11] Spending Too Much Money on a Coding Agent - Allen Pike

https://allenpike.com/2025/coding-agents/

[7] Without good tooling around them, LLMs are utterly abysmal for pure code generation and I'm not sure why we keep pretending otherwise : r/ChatGPTCoding

[8] Beyond Code-Centric: Agents Code but the Problem of Clear Specification Remains

https://www.gregceccarelli.com/writing/beyond-code-centric

[14] The emerging impact of LLMs on my productivity

https://www.robinlinacre.com/two_years_of_llms/

[17] [19] [20] [23] 7 Proven Strategies to Cut Your LLM Costs (Without Killing Performance) | by Rohit Pandey | Medium

[18] [21] [22] Is your LLM overkill? - by Ben Lorica 罗瑞卡 - Gradient Flow

https://gradientflow.substack.com/p/is-your-llm-overkill

[25] The coming explosion in QA testing

https://charlesrubenfeld.substack.com/p/the-coming-explosion-in-qa-testing